What’s for dinner?

June 14, 2016

By Scott Nichols

Somewhere near the middle of the century there will be 2 billion more of us on the planet. That’s a very big number of new folks to feed. Beyond numbers, the composition of the population will change as well. The world is experiencing rapidly increasing wealth and with increased wealth comes change in dietary preferences. The larger and wealthier population we will have mid-century requires we roughly double our food production (see here and here). Quite soon, an unprecedented demand will be placed on our food system.

Our current agriculture uses 38 percent of the land and consumes 70 percent of available water. Can we double 38 percent? No we can’t, at least not from a practical point of view. As for doubling 70 percent—it simply isn’t going to happen.

Doubtless there will be improvements in agricultural productivity. These are likely to be incremental improvements and, while they are important, they will not take us where we need to go. Large and discontinuous improvements are needed—revolutionary not evolutionary change.

The Fish We Eat

One thing we can do is to turn to the sea but we need to in a particular way. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations undertakes a biannual oceans assessment called State of Worlds Fisheries and Aquaculture. The 2008 report found 80 percent of fisheries harvested at or above their sustainable limits. Successive reports were increasingly grave until the 2014 edition showed 90 percent of wild fisheries are harvested either at or above their sustainable limits so it isn’t feasible to capture more wild fish. More likely, wild fish capture should probably decrease to allow challenged stocks to replace themselves.

Whether wild fish harvests decrease or remain the same, however, they will certainly not address increasing demand. It seems clear that if we are going to continue to eat fish, we need to farm them.

Aquacultural Productivity.

The encouraging news is that aquaculture is capable of providing the new and discontinuous change we need. Its potential productive capability is tremendous. Here’s an example of that.

Duplin County in North Carolina in the US produces lot of hogs. With its 822 square miles and 59,000 people Duplin County produces more hogs—about 2 million per year—than any other county in the nation. The result is about 280 million pounds of marketable pork.

What size of fish farm would be required to match the hog production in Duplin County?

Picture, if you will, a fish farm whose nets are 15 meters deep. In those nets the amount of fish is held to a maximum of 5 kg of fish per tonne of water or, said another way, the fish occupy one half percent of the volume of the pen. (By comparison, national regulations for salmon farms in Norway are that fish not exceed 25 kg per tonne of water so what I’m talking about here is a 5 fold reduction.) Add the further stipulation that half of the weight of fish grown actually is fish that makes it to market.

The length of the North Carolina coastline is 484 km (301 miles) making US territorial water off North Carolina 156,000 square km (60,200 square miles). The amount of ocean surface required to raise 280 million pounds of fish on our thought experiment farm is 01.6 square km (0.6 square miles).

This comparison is loose; of course all of the land in Duplin County isn’t a hog farm. But you can see that aquaculture’s productive capability is enormous.

Resource Requirements

The animals we eat must also be fed themselves and a very large part of the environmental footprint for animal agriculture is growing what they will be fed. Animals use the calories they eat to fuel growth and to provide for their day-to-day metabolic activity. To a first approximation, animals that eat less will have less impact on the environment.

Metabolism is an area where terrestrial animals and fish differ in three very important ways.

- Fish are cold blooded so they don’t need to spend any energy to maintain their body temperatures. Farm animals on land, however, need to devote the energy from some of what they eat either to heat or cool their bodies when the air temperature is different from body temperature.

- Because fish live in a weightless world; by being suspended in water they don’t use any energy to fight the endless battle against gravity land animals continually face.

- Lastly, because they don’t have to deal with gravity, fish don’t use the calories they eat to build the extensive and heavy skeletons required to keep land animals upright. This has two practical outcomes. Fish don’t spend their energy to make big gravity-resisting bones and, with their comparatively smaller skeletons, fish provide considerably more food per kg of animal raised than their counterparts from the land.

These things—cold-bloodedness, life in a weightless environment and much smaller skeletons— mean fish can be raised with a lesser call on resources to feed them than the other agricultural animals we raise.

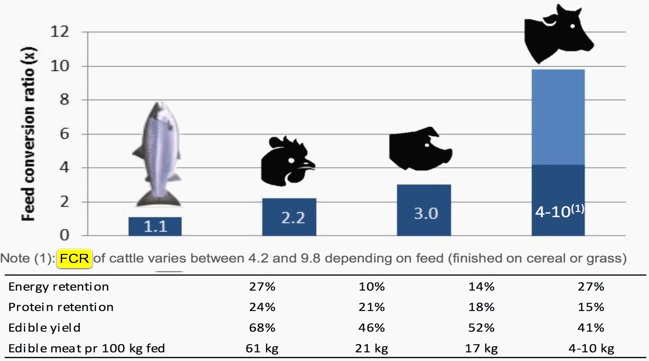

This is, perhaps, best seen in what is called the feed conversion ratio (FCR). FCR is the amount of food required to raise an amount of animal. For instance, it takes about 1.7 kg of feed to raise a kg of tilapia and only 1.2 for a kg of salmon. On land, however, beef cattle have FCRs of 6-10 depending upon how they are raised while for chickens it is about 2.

Reference to salmon:

Chart by Marine Harvest

Lower FCRs and the higher percent of the animal eaten are what led Conservation International and The WorldFish Center to conclude in their 2012 report Blue Frontiers

“It is apparent from this study that aquaculture has, from an environmental impact perspective, clear production benefits over other forms of animal source food production for human consumption. In view of this, where resources are stretched, the relative benefits of policies that promote fish farming over other forms of livestock production should be considered.”

How Your Food Is Raised Matters.

All agriculture, whether on land or in the ocean, has environmental effects. Therefore the measure of proper stewardship isn’t having no effect. Rather it is to avoid negative effects to the greatest extent possible and then to ameliorate the rest. A laudable goal is to raise food now with practices that don’t preclude others from doing so in the distant future.

To ensure pursuit of the most responsible aquacultural practices, the World Wildlife Fund established a series of discussions called the Aquaculture Dialogues in 2004. Participants came from many stakeholder groups—farmers, NGOs, scientists, retailers and other aquaculture-associated businesses¾to define best practices and, from them, develop standards for responsible aquaculture for 12 different species. The standards were then passed on to the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) which trains independent auditors to examine on-farm performance and certify farms whose practices comply with the standards.

Certification against ASC standards means a number of different things for us as consumers. Most importantly, it lets us know that our food was raised with responsible practices that ensure the healthfulness of the fish we eat and the health of the environment where they were raised.

Because, how our food is raised truly does matter.

© Scott Nichols, Food’s Future